During my founding years as a miner (1990 to 2000) I had learnt early on and in the hardest of ways to do the right thing (or face the consequences) on the South African gold mines at Freddies #5 shaft (later called Matjhabeng Mine) from 1990 to 2000 as a stoper, developer, night shift cleaner and shift boss, in the Northern Free State Gold Fields – where the ore was all broken up and scattered, and where few of the Transvaal (a province in the old South Africa) miners ever came to work because it was too challenging.

During that time, I became a high-grade pillar extraction specialist (mining the under pressure leftover pillars that everyone ran away from years before because they were too afraid to take it out and because there were too many other easy ground to go to). I did most of that on Freddies 5 shaft. The workers knew this shaft as the killer mine because it budgeted for between 12 to 16 fatalities per year just for that one shaft. We hoisted 2500 people up and down that shaft every day and employed 36 shift bosses divided into nine superintendent production sections. The shaft was equipped with 4x man cages and 4x huge skips for conveying rock, and a Mary-Anne service winder. It hoisted 250kt of ore per month from an average depth of 1.6 km below the surface.

I worked at that shaft for just over five of my ten years on South African gold and never had a fatality on my beat. Still, it took a hell of a lot of commitment and balls to achieve that because you had to always do the right and best thing to ensure safety, and sometimes it meant stopping production to ensure safety, and with a ‘three failures and you’re out policy’ that never came easy.

Though there were also deaths, but not due to my failure, e.g. we lost one of my drillers there in 49 W2 48 panel 18 when I left to get married on 01 October 1994. The shift boss who relieved me ignored my instructions and pushed the stope face too far without support, and it collapsed. Everything was handheld drilling back then, with my drillers right there on the working front, so it was inevitable that one would be caught in the fall of ground.

Now, I haven’t even gotten started talking about my mining experiences in 90 degree vertical overhand stopes – very stressful and risky, but the best mining I’ve ever done (because gravity cleaned the face for you in under 20 minutes after a blast, with small amounts of water added, and if you angled the slope of the underhand stope face correctly you could also walk on it and the drillers could drill down into it like in the bottom of a sinking shaft using gravity to push their rock drills into the rock). Even though I took great care to protect myself and my people, I also had my own close shaves there, e.g. I had to dig myself out twice from collapsed stope panels (with the help of the gangs who was also caught behind the falls of ground). I also got stuck once against the back while caught up in a rock slide that built up around me. Also lived through a mud rush that filled the crosscut up to chest height, also almost got gassed twice, the first time is a long story, and the second time happened while my miner and I got lost in back areas as we were seeking to find abandoned double drum Sullivan and Pillman winches. I, at that stage, trusted my miner/stoper to know the back areas, so we entered without maps/plans (which was an accepted practice used to follow paths along survey pegs on the plans and in the workings). Sadly after entering the old area, I had to discover the idiot got us lost. I, at that stage, then had to revert to saving our asses from certain death when we eventually ended up in an abandoned and unventilated walled up old crosscut (as I followed my miner into almost certain death). I got us out of there that day by knowing our mining methodology and the natural dip of the orebody, which provided me with some direction as to head in. We went through areas we’d never been in before that day, but it led us back eventually to our well-ventilated workings. That was my closest shave ever, and that day it took all of my wit to get us out of that situation. The old or back areas at these mines were so vast at 1.6km underground that they connected three towns 20km apart, e.g. Odendaalsrsus, Welkom and Virginia, to a lesser extent.

Founding years:

My founding years as a miner maturing towards a mining engineer took place while I was employed with AngloGold Ashanti, back then known as Anglo American Corporation, Gold Division. During this time most of my experience was gained in the very challenging underground mining conditions of the Northern Freestate Region of South Africa’s deep-lying gold basin deposits. As a development miner and a production stoper, e.g. a junior official maturing into a shift boss and transitioning into a mining engineer, I gained conventional or ‘old-school’ mining experience while developing horizontal crosscuts, haulages and return airways outfitted with conventional railway infrastructure; this development experience further extended into minor and steeply dipping raises, winzes, finger-raises and vent-drives, and also steeply dipping travelling ways, box holes and ore-passes. The experience I gained also extended into the production stoping of narrow and wide gold-bearing ore seams laying on minor to near-vertical dips. This wide variety of different ore deposits at depths ranging from 1.5 to 2 kilometres below surface gave me the opportunity to experience a vast amount of different mining methodologies while practicing conventional ‘longwall type’ stoping methods in virgin ground conditions and scattered mining methods as a remnant or pillar extraction miner and shift boss. My experience with different stoping methods includes undercutting (down to 85 centimeter working heights) and open stoping up to 3 meters high or wide (while employing roof bolt, elongate and mat pack or concrete support units). These stoping experiences included steeply dipping shrinkage mining practices in an overhand configuration and vertical underhand mining practices. During this time I took grade pride in my experience gained as a remnant or pillar miner and shift boss in extremely difficult ground conditions. These experiences included multiple successful stope face re-establishments following tear-offs along the stope panel face under extreme stress conditions; also the recovery of lost ore-horizons (caused by minor fault throws) by doing prospect development using finger-raises to find ore locations again. My stoping experience as a miner and shift boss also extended into stope establishment, also known as stope ledging practices, which was considered a specialised skill set mastered only by a small number of stopers. All these experiences were gained in fiery (methane bearing) mines with very high fatality frequency rates, and I take great pride today in that I maintained a fatal free safety track record throughout this time and while working as a miner and supervisor in the areas of the mine with the highest risk of harm.

As a production shift boss, my biggest crew consisted of a 120 people including 3 stopers, 6 team leaders and an equipping & salvage team leader with his crew of 5 men. As a production shift boss and miner, I was also responsible for a rigging crew (used for winch relocations) and night shift cleaners.

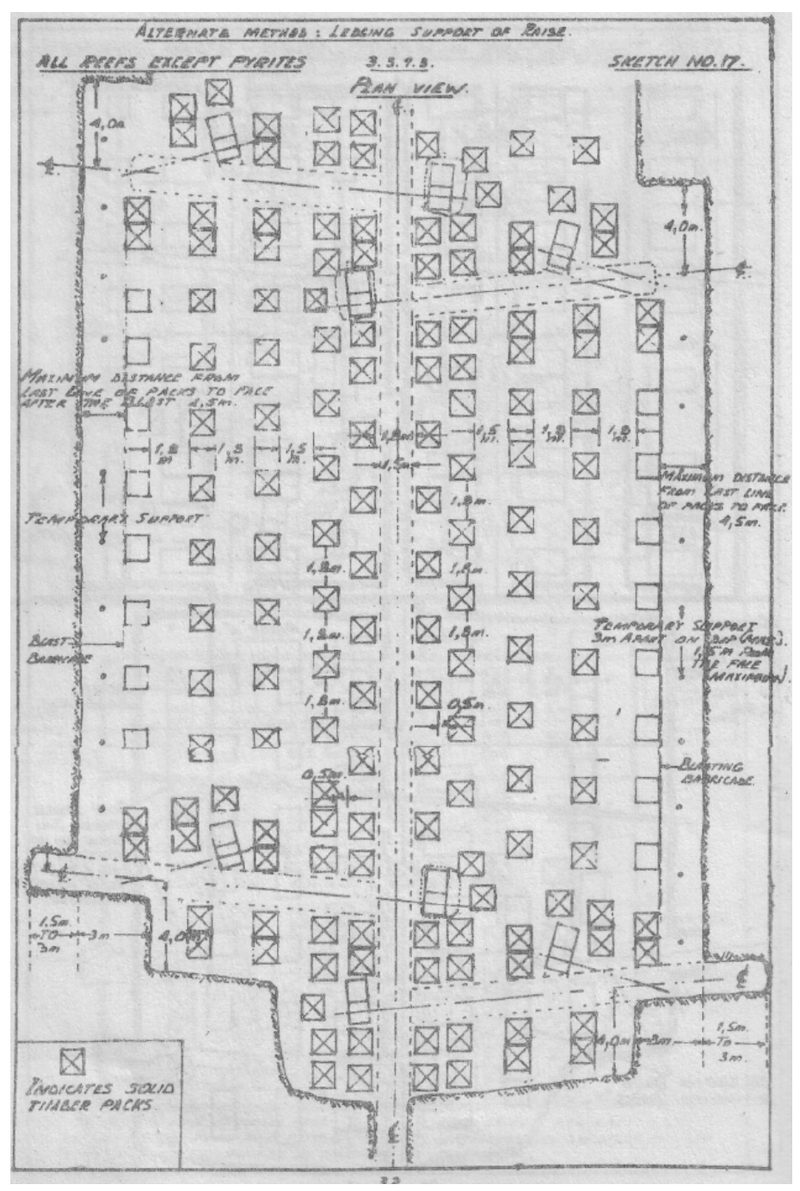

The below PDF file below provides some idea of the working environment I described above.

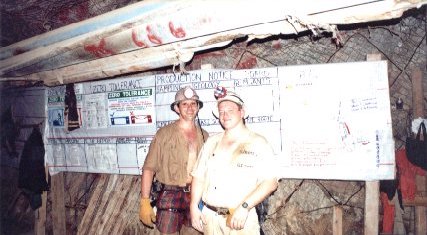

Below is a photo of me with another miner at Freddies #5 Shaft.

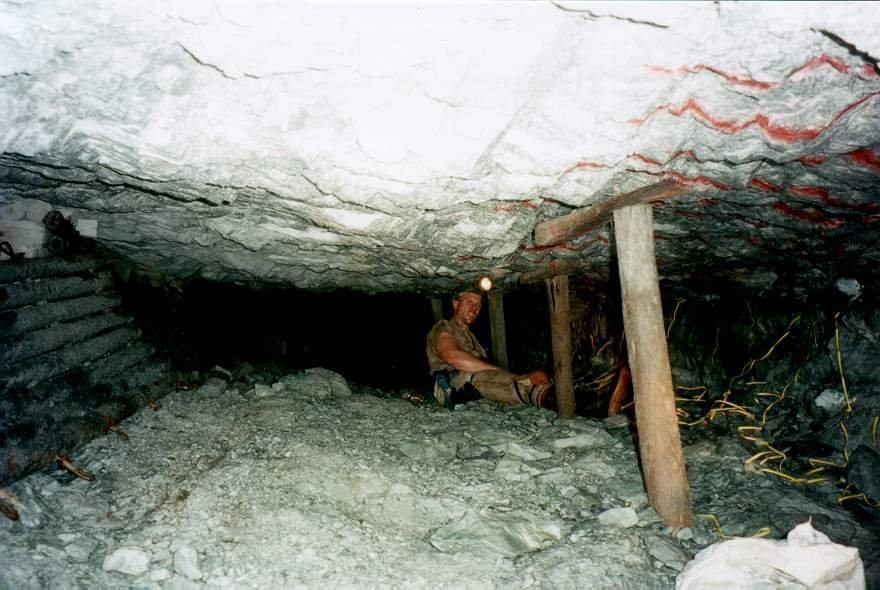

Included below is also a photo taken in a breast stope at Freddies #5 shaft.

Plan view of stoping standard in narrow tabular breast mining.